How much of your life do you consider blind luck, and how much do you attribute to the choices that you’ve made?

Muslims are by their very nature fatalists. They believe that what is ordained is ordained; and no one but God can alter anything. Each event, small or large, long before it ever happens, is written in The Book. My former husband, true to his faith, chalked up his terminal cancer entirely to mektoub.

When he was diagnosed with stage-4 colon cancer, his doctor implored him to change his habits, but Hakim wouldn’t have it. If God had determined that it was his time, he reasoned, nothing he could do would change the outcome.

All throughout his illness I blamed Hakim. I judged him harshly. He was a man with a fighting chance, who frittered it away by eating steak and greasy rice, who drank gallons of black coffee and smoked until one couldn’t make out the furniture through the smog. A man who ignored the miracle herbs his niece sent him from Canada, and the books from friends on restorative nutrition. To my way of thinking, he was a man with two young children who needed him desperately, and he wouldn’t do a goddamned thing to try.

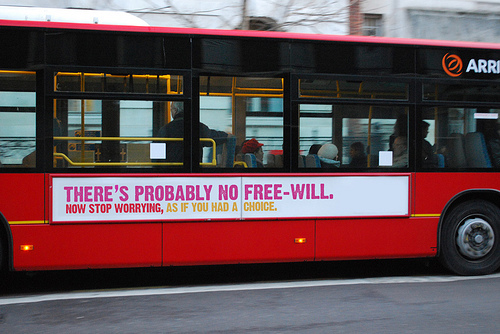

Free will, I will remind you, is our God-given right to choose. I, however, didn’t like the choices that Hakim made.

All throughout his illness I also blamed myself. I was a woman who had absconded with his kids, who’d dragged him back to the States after he’d given up everything he held important, only to dismiss him. Dejected, it was only natural, if one believes that emotions determine health, as I do, that he would get sick and then die a horrible death. It didn’t matter that he smoked two packs a day. I’m the one, I thought, who’d killed him—not the tobacco companies, not the doctors who’d misdiagnosed him— because he was never able to let me go.

While debating the clashing philosophies of free will v. Fate one day, Hakim reminded me of the pedestrian way one of our friends had died. Parveez had been a man so reckless in his dealings (he’d once escaped Iran in the trunk of a drug-smuggler’s car), so casual with danger; he should have been killed a thousand times over. Instead, he’d set out to change a flat tire in an English driveway one morning only to have his head crushed by his car when the jack slipped out. “Tell me,” Hakim had said, “if anybody but God could have planned an end like that.”

For a while I thought that maybe Hakim had been right; maybe it’s better to surrender, to accept life in the form it’s delivered, and stop railing against the injustice of it all.

Then, after a few years of watching others fall apart, or put themselves back together again, I decided that the life we buy ourselves tends to be the result of a series of choices, of actions and reactions, with a little bit of luck—good and bad—thrown into the mix. It’s why my mother-in-law, years after her doctor warned her about inactivity, sits crumpled in a wheel chair with rheumatoid arthritis. It’s why my friend, Anne, nearly the same age, made a full recovery from a crushed pelvis four months after her rock fall. Two women blessed to be alive who made a lifetime of very different choices.

And while I agree with those who say, “If you want God to laugh, tell her your plans,” I also believe that we are the head architects of our own life. It’s not free will or fate; it’s both.

Life is about choices, good and bad and sometimes not even that. Sometimes they aren’t good or bad, they’re just choices that are the best you can do at any given time.

What choices—not just for your health, but for your finances, career, and relationships—will you make today that will allow you to enjoy, or prevent, those things you can control? Or have you decided that what happens to you is already written in The Book?