As much as we’d like them to, our readers don’t tend to remember strings of concepts, statistics, or cold, hard facts. Especially page after page of them. The best way to make information sticky is to tell them a story, to deliver the necessary points, at least the major ones, within a scene.

One of the most important elements of scene is dialogue. Dialogue, in case you’re not familiar with the term, is what two or more people (characters) tell each other as they banter back and forth. It’s the stuff that goes inside quotes.

All this being said, I’m going to give you a little tutorial on writing dialogue simply because I care about you, and my eyeballs. (There are days, that’s all I’ve got to say.)

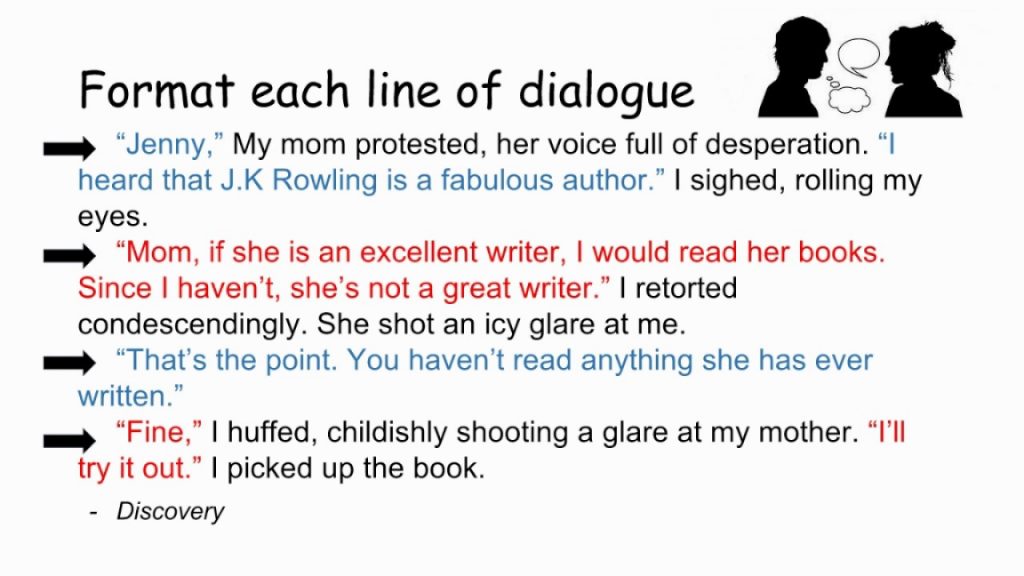

First things first. We’ve got to format our dialogue on the page properly if we want to look like we know what we’re doing. There’s a standard way of doing that that looks like this:

Notice that each time a new person starts to speak, a new paragraph is created, complete with indent. First, we have Mom speaking, then we have Jenny, then we have Mom again, then we have Jenny. (Note: Jenny sounds like an asshole.)

This formatting tells the reader that we’ve got a conversational tennis match going, which player is taking the swing.

Also, notice that the punctuation marks go inside the quotation marks. (By the way, there’s so much wrong with this dialogue I want to scream, but I’ll get to that in a minute.) We’ve got the comma inside the quotation marks, which separates out what is being said from who is saying it. We’ve got the period or question mark inside the quotation marks that lets us know the speaker has finished a sentence or a question. And so on.

Now, let’s get to all the shit that’s wrong in this here example. (Before I get going, it should be ‘my mom,’ not ‘My mom,’ but that’s neither here nor there.)

1. You don’t want to keep inserting names in dialogue. It doesn’t sound natural. We don’t need Jenny or Mom up front like that. This is part of the reason these people sound like jerks because real people don’t talk like that. For example, when I’m having a conversation with Walt, it does NOT go like this, unless we’re really pissed at each other:

“Walt, I really wish you’d stop reading while I’m talking to you. This is important,” I sighed.

“Ann, I’m not reading, I’m paying close attention to every pearl of wisdom coming from your lips.”

“Walt, you’re lying. I always know when you’re lying. And this, Walt, is one of those times.”

Most of the time we’re worried our readers won’t know who’s speaking, that’s why we toss in those names, but that formatting thing I just taught you, that does the clarification job an awful lot of the time.

2. If you need to use a speaker attributions for the purposes of clarity, use “said.” It has a much lower profile than words like whimpered, hissed, inquired. If the dialogue is well written, these are not necessary.

Which is another reason I find myself hating Jenny and Mom. They sound spastic. We’ve got Mom protesting. We’ve got Jenny retorting and huffing. I mean, doesn’t that make you want to slap them?

Looking at the example above, notice that third line. We know that’s Mom speaking because of the formatting. We don’t need to add, Mom yelled or Mom howled or any such nonsense.

3. Resist the urge to explain

“Since I haven’t, she can’t be a great writer,” I retorted condescendingly.

Jenny’s words already show condescension—there’s no need to explain it. We can already see that Jenny needs a major timeout by the words coming out of her mouth. Or a boarding school for the defiant.

You can make sure the dialogue shows the emotional state of the speaker or you can use a scene tag.

I’ll explain what I mean by a scene tag by way of an example:

“Since I haven’t, she can’t be a great writer.” I picked up the Harry Potter volume Mom had set on my desk and spat on it before tossing it out the window.

And one other thing here. Avoid ‘ly’ words. These are adverbs. Adverbs are pretty much a no-no. Get rid of them. Think of them as corn syrup and other crappy stuff you need to remove from your diet because they do you ZERO good.

“I don’t like onions,” Walt said harshly.

Instead of using the adverb “harshly,” make his words harsh, or use a scene tag, or use a stronger verb: detest, loathe and abhor have some juice to them.

“I fucking detest onions,” Walt said. (Better, right?)

(While we’re on the subject, examine all verbs to see if they can be strengthened. Walt walked across the room does not give us a visual image, but verbs like bolted, crept, trudged, scampered or darted do. Walt pranced across the room. Whole other feel, don’t you think?)

4. Avoid freighting information in dialogue: Trying to insert background information into a character’s mouth will sound forced as well as awkward.

“Oh, Mom. It’s so good to be here again. Can you believe that this cottage has been in our family since 1920, three whole generations, and we’ve been here every summer since I was one? And you’ve been trying to have me embrace J.K. Rowlings since you had an affair with her in 1999, which started right on that porch over there.”

No one talks like this. This is all about the writer not knowing how to give the reader the necessary information without having it come out of someone’s mouth. Just say no to this bad, bad practice.

5. Avoid over dramatizing as I’ve done in most of these examples.

I mean, what’s with Mom’s voice being full of desperation? For God’s sake, why does she need Jenny to embrace J.K. Rowlings for the brilliant writer she is? Will Jenny go straight to hell if she doesn’t, get sent to Ryker’s Island?

Hope this helps.

_________________________

If you liked this little snippet, you’re going to love THE BOOK. Learn all of the dance steps you’ll need to master in order to write a powerful, publish-worthy book.